Cologne Cathedral and 'The Jews'-The shrine of the Magi

The shrine of the Magi was created sometime between about 1190 and 1220 to house the relics of the Magi (Three Wise Men, Three Holy Kings), which were brought to Cologne in 1164.

Surprisingly, only the images at the front end of the shrine are devoted to the Magi, whose relics are concealed within. There we see a depiction of the adoration of the Magi, who came to pay homage to the 'newborn king of the Jews', and are only mentioned in Matthew's Gospel (Matt. 2: 1–12). From the sixth century onwards, these pagan magicians—or wise men—were portrayed as kings.

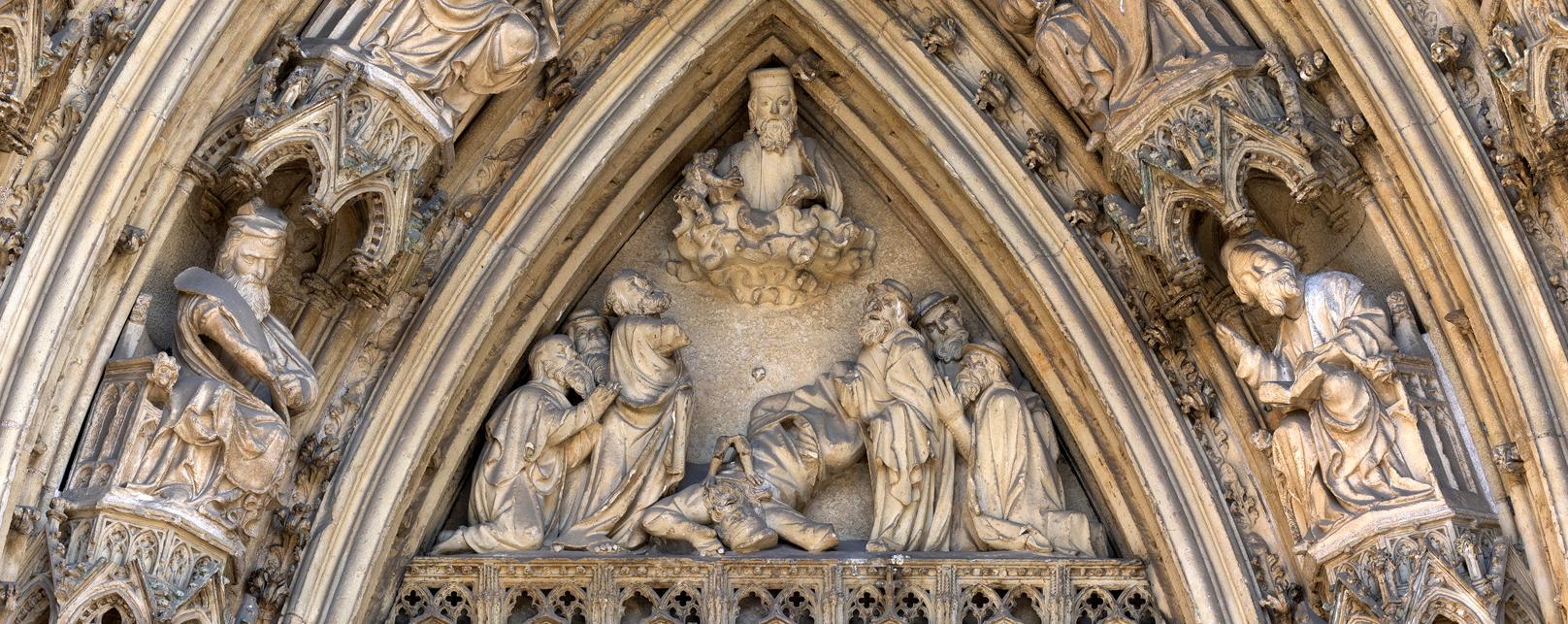

The central theme of the images on the shrine is the history of salvation which, according to the Christian interpretation, centres on Jesus Christ—from Creation to the Second coming of Christ at the end of time. This explains why the prophets are depicted in the lower arcades on the sides of the shrine, starting with Moses. The prophets can be seen on either side of Kings David and Solomon. The apostles above them highlight the link between the Old and New Testaments, but are at the same time an expression of hierarchy in the spirit of Christian typology.

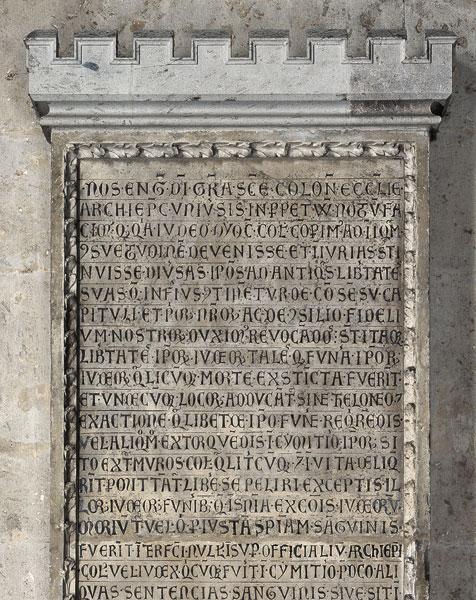

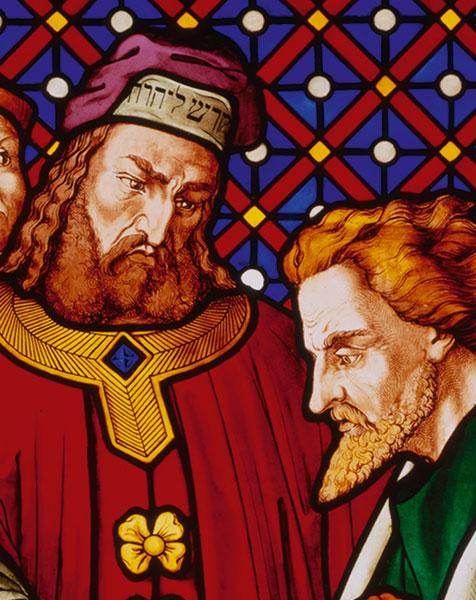

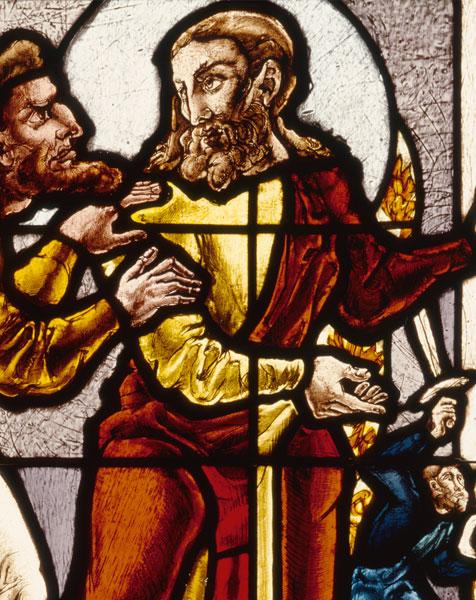

The back end of the shrine, which was created in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, features not only a traditional depiction of the crucifixion with Mary and John, but also a highly controversial depiction of the Scourging at the Pillar. Instead of the Roman soldiers mentioned in the Gospels, Jesus is scourged by two thugs carrying rods who are clearly identifiable as Jews from the conical hats they are wearing.

The inscription on the gable, which translates as 'The true victim, Jesus, was spat on and struck with blows', provides an important indication as to the interpretation of this image. This text alludes not only to the flagellation of Christ by Roman soldiers commanded by Pontius Pilate, which is described in the Gospels, but also to the fact that Christ was spat on and beaten by some of the chief priests, elders, and scribes of the Sanhedrin, the Council, mentioned in Mark's Gospel (Mark 14: 65 and Matt. 26: 67).

From the early twelfth century onwards, this scene, which insinuates and describes in images an active involvement of the Jews in the death of Christ, appears with increasing frequency in portrayals of the Passion of Christ. Early Christian writings and sermons, which blamed the Jews for Christ's murder, paved the way for this view and culminated in the allegation of deicide as early as the second century. In addition, from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries onwards, the Jews were seen less as individuals and more as a group to which collective liability was apportioned. Moreover—and this is something that is more fatal with regard to the image here—contemporary Jews are equated with those described in the New Testament.

Harald Schlüter

The depiction of the prophets on the sides of the shrine begins with Moses carrying the Tablets of the Law, engraved with the first words of the narrative of Creation from the Book of Genesis, the first book if the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), in Latin.